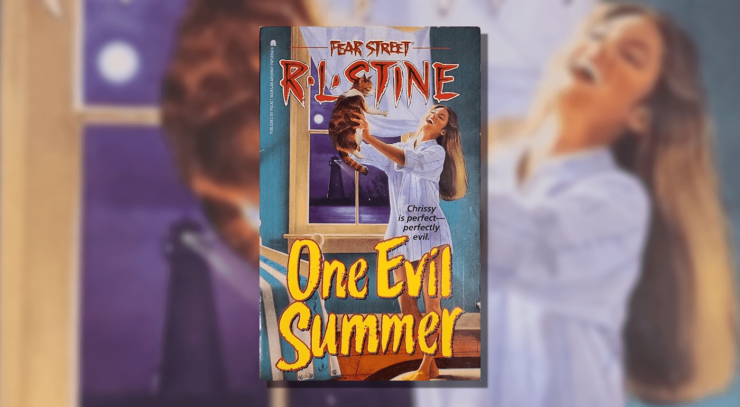

There is no shortage of bizarre stories and credulity-straining plots twists in ‘90s teen horror books: adults masquerade as high school students (R.L. Stine’s Halloween Party), teens take unsupervised spring break trips to Hawaii (Christopher Pike’s Bury Me Deep), and there are all manner of convoluted murder plots, revenge schemes, and supernatural dangers. But R.L. Stine’s Fear Street book One Evil Summer (1994) really stands out, with a smorgasbord of wild and wacky plot developments that keep the reader unsure of just where the next unbelievable turn will take them and what kind of story this actually is. Is the danger grounded in the real world or supernatural? Can we trust the main character Amanda’s perceptions? Is babysitter Chrissy Minor an innocent victim or an evil monster? Stine provides readers with competing clues, withholds information, and throws red herrings everywhere, making One Evil Summer one of the oddest novels of the ‘90s teen horror cycle (a remarkably high bar).

From the opening pages of the book, Stine plants the suspicion that we may not be able to trust Amanda’s recollections of her terrifying summer. In the first chapter, Amanda is in Maplewood Juvenile Detention Center, accused of murdering her family’s summer babysitter, Chrissy, with most of the book framed as an extended flashback. When One Evil Summer starts, Amanda has been in the detention center for three days, with her lawyer and the center’s psychiatrist asking her the same questions over and over, though no one actually seems to listen to or believe her answers: “What had happened? What had she been thinking? How had she been feeling?” (4). It doesn’t seem like anyone believes what Amanda has to say and she has even started doubting herself and her own senses, thinking “Maybe I do belong in here” (4, emphasis original). With this opening chapter, Stine sets Amanda up as an unreliable narrator, encouraging the reader to engage with the story through this lens of doubt and the possibility of Amanda’s guilt, a perspective that is reiterated multiple times throughout the book itself. When Amanda tries to tell her parents she saw Chrissy floating in mid-air, they dismiss it as a dream and when she tries to warn them that Chrissy is dangerous, they drag Amanda to a therapist named Dr. Elmont to deal with what they identify as unresolved jealousy toward Chrissy.

According to Dr. Elmont, the jealousy Chrissy feels can all be traced back to algebra: Amanda failed algebra during the regular school year and now has to retake it in summer school. Amanda’s family is on a summer vacation, leaving Shadyside behind for the beach community of Seahaven, which means she’s retaking the class in a new school, with students she doesn’t know, and her vacation is divided between algebra in the morning, hanging out with her younger brother and sister Kyle and Merry in the afternoon, and trying to survive living with Chrissy in every spare moment in between. Dr. Elmont’s professional hypothesis is “Maybe somewhere deep inside, you think you don’t deserve your parents’ love anymore since you failed algebra. Maybe you think Chrissy is taking your place, and you hate her for that” (83). These seem like really high stakes for a high school math class (and definitely not helpful in addressing perceived ability, self-efficacy, and gender gaps in STEM), but everyone seems to seriously think this is the main cause of Amanda’s stress and struggles.

Apparently, algebra-related stress can cause some pretty wild hallucinations and persecution complexes, because the interactions between Amanda and Chrissy start weird and only get weirder. When the girls first meet, Amanda’s cat Mr. Jinx hisses at Chrissy and Chrissy’s eyes glow as she hisses back at him, terrifying the cat. When Chrissy is playing in the front yard with Kyle and Merry, a car inexplicably careens out of control and kills Mr. Jinx. Chrissy is cagey about her family, saying she lives with her aunt nearby, though no one in Seahaven knows her and when Amanda calls her out on the lie, Chrissy says it’s basically true, it’s just that her aunt hasn’t moved into the house she wrote down as her address yet. Her parents are dead, though her story of how they died changes, depending on who she’s telling it to, and her sister Lilith is either dead or in a coma, but these details change from one account to the next as well. Chrissy has a collection of newspaper clippings about her family, but when Amanda goes to Chrissy’s room to try to find them, she encounters numerous obstacles, including seeing Chrissy floating in mid-air and laughing. When Amanda calls her friend Suzi Banton back home and asks her to go to the Shadyside library to look for information on Chrissy, like newspaper stories about her parents’ accident, the phone melts in her hand and Chrissy’s maniacal laugh echoes down the receiver. Suzi heads to the library to help Amanda out, but is later found “slumped over on the microfilm viewer, blood pouring from her mouth and nose” (91), taken in an unresponsive comatose state to the hospital. Amanda’s mom can’t get ahold of Chrissy’s references but takes a chance on her and after a while, forgets all about following up. When Amanda decides to try to contact them herself, someone finally answers, telling Amanda “I’m just a neighbor … We were wondering why we hadn’t seen the Harrimans in so long. You won’t believe what we found. I—I’m sorry. I think I’m going to be sick” (95). The call is cut short and Amanda never finds out the specific horrors of the Harriman house, though the girl on the other end panics when Amanda tells her that Chrissy is her family’s new babysitter, saying “Chrissy is in your house?! … Oh, no! Get out—now!” (96), before hanging up on Amanda. This all seems like an awful lot of terror and trauma to stem from a failing algebra grade, but as far as the adults in the book are concerned, it can all be traced back to those pesky equations.

Everyone who believes or tries to help Amanda ends up either incapacitated or dead. Suzi is in a coma back in Shadyside and the only person on Amanda’s side in Seahaven is a cute boy named Dave from her algebra class. He believes Amanda and is willing to help however he can, even luring Chrissy away from the house to check out his car or take her to the movies in order to give Amanda the time she needs to look around and try to collect evidence. (Chrissy seems excited about these opportunities, figuring that she’s stealing Amanda’s boyfriend, though in the larger scheme of things, this doesn’t really seem like all that big of a deal). Just like readers are encouraged to doubt Amanda’s perceptions and reliability, Dave remains a bit of an enigma. He takes Amanda on a jet ski ride out to an island to an abandoned hunting cabin where he and his brother like to hang out, showing her bloodstains on the floor, a doomsday prepper-style cache of dried food, and a big hunting knife that he suggests they use against Chrissy, planting it in her room to get her fired (though Amanda at first thinks he means murder). Dave seems stalwart and supportive, but also comes with plenty of red flags. That all becomes inconsequential when Chrissy figures out that Dave and Amanda are on her trail and magically pushes Dave’s parked car over a cliff. Amanda escapes but Dave plunges to his death. The cops come to Amanda’s house looking for him after his parents report him missing, but his car is never recovered, his body is never found, and he’s pretty much never mentioned again, either with regard to the tragedy of his death, justice for his murder, or Amanda’s grief.

The nature of Chrissy’s abilities are a fluid bait-and-switch throughout the book, as readers work to figure out whether she actually has magic powers or if Amanda is hallucinating, whether the threat Chrissy poses is human or supernatural. The answer is (kind of) revealed when Amanda finally gets her hands on the clippings Chrissy has been hiding, which include a direct link between Amanda and Chrissy’s families, stemming from an incident in which Amanda’s father, who is a public defender, was instrumental in Chrissy’s father being charged with arson after he set his own office on fire. (Harriman was the judge in the case, making him Chrissy’s previous target and employer). When the pieces all fall into place, Amanda discovers that Chrissy is actually Lilith and was in a coma following her parents’ murder-suicide deaths, and doctors note that she “somehow assumed strange new powers while in the coma” (161). That’s the extent of the explanation: somehow this unbelievable thing happened, with the professionals later using the sheer unbelievability as justification for why they didn’t believe Amanda, even though everything she told them was true.

Amanda and Chrissy are drawn into a final, violent confrontation when Chrissy kidnaps Kyle and Merry, intending to kill them. Amanda rescues her younger brother and sister from drowning when Chrissy takes them out in a boat, knocking Chrissy unconscious. When Chrissy comes to and continues to try murdering the three siblings, Amanda keeps them all safe, despite the fact that Chrissy has set the house on fire and is using her inexplicable powers to bombard Amanda with miscellaneous items from around the house. In the end, Chrissy gets her comeuppance when she trips over a stray kitten and falls face-first into the fire. Amanda has saved the day, as well as Kyle and Merry’s lives, though when the police show up, she is arrested on suspicion of Chrissy’s murder and sent to the detention facility where readers first meet her in the book’s opening chapter.

No one has believed Amanda throughout One Evil Summer and as she tells her story again in the detention center, they still don’t believe her. No one corroborates her story or comes to her rescue. Her parents doubt her, Merry is too young to be able to tell anyone what happened, and Kyle has been struck mute with shock from the trauma he has endured. Amanda is hopeless and defeated, telling her psychiatrist “what’s the point? I’ve told this story about a hundred times, but no one believes me” (160). He reviews all of the reasons why everyone thought she was guilty and all the ways in which her story is unbelievable, overtly framing her as unreliable and untrustworthy … before telling her that Kyle has regained his ability to speak and has come to Amanda’s defense. The psychiatrist justifies and defends the fact that no one believed her as a preface to his revelation that “Kyle is much better. He began speaking this morning, and his story does match yours” (160). As a teenage girl, Amanda herself is unbelievable, but when her eight year old brother vouches for her, it’s all good.

In the end, while Amanda is thankfully vindicated, lots of lingering questions remain, drawing readers back to a plethora of loose ends and wild twists that ultimately lead nowhere: Was Dave a good guy? Did they ever find his body? Did Suzi ever wake up? Are Chrissy’s coma-induced supernatural powers indicative of a larger trend or threat? What is the hero kitten’s name? Did Amanda pass algebra? We’ll never know.